Have you ever watched a pitcher throw during a baseball game and wondered how he got the ball to move the way it did? How does Justin Verlander throw his 100 mph fastball? Want to know how Mariano Rivera gets his cutter to dart and break bats? We’ve got you covered.

Now pitchers are tinkers, always fiddling around with different grips and pitches. There is more than one way to grip all of these pitches, but the basics are still the same. Read on to find out how to throw the various pitches used by today’s major league pitchers.

Four-seam Fastball

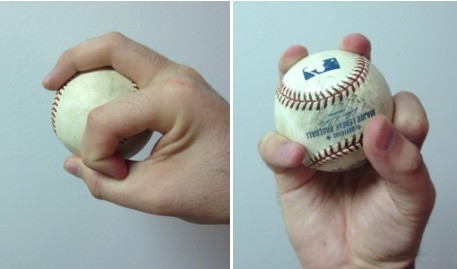

The four-seamer is the most basic pitch in the game. It’s simple, but effective. When you hear baseball people talk about a pitcher “bringing the heat” or “throwing gas”, they’re talking about a four-seam fastball. It has the highest velocity of any pitch, and the hardest throwers– those who can throw the fastest speeds– throw four-seam fastballs. There’s no subterfuge with this pitch; it’s just “here it is, see if you can catch up to it.”

Most baseball fans would assume guys like Tim Lincecum and Clayton Kershaw,who utilize the four-seamer, would throw pretty hard. And you would be right as most usually throw mid- to upper-90s.

“Power” or “strikeout” pitchers generally throw a four-seam fastball. The downside to this pitch is that it doesn’t move much, meaning that if a hitter times the pitch right, he stands a good chance of hitting it.

Power pitchers tend to give up more home runs because the extra velocity on their fastball results in more power coming off the bat if a hitter squares the ball up. The faster a pitch goes in, the faster it comes out.

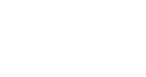

The four-seamer is also the easiest pitch to throw. Grab a baseball and find the horseshoe. Now, I always hold mine with the curve of the horseshoe to the left of my index finger, but you don’t have to. Place the tips of your index and middle fingers on the top seam with your thumb down below. I tuck my thumb under so that the seam runs from my knuckle to the tip, but that’s just personal preference.

When the ball is in flight, you can see all four seams; hence the name. When you throw, you want to keep your hand behind the ball rather than underneath it (basically don’t cock your wrist back), and then just snap your wrist at the end.

Two-Seamer

The two-seamer doesn’t have the same velocity as a four-seam fastball, but it has a lot more movement. Two-seamers are typically in the 88-92 mph range. A few pitchers can throw one in the mid-90s, but it’s rare.

A sinker is a two-seam fastball. The purpose of this pitch isn’t to make the batter miss. The pitch is designed to be thrown low in the strike zone to take advantage of its downward movement. If a batter does hit it, he’ll most likely just beat it into the ground and produce a groundball.

Sinkerballers want batters to put the ball in play. As a result, they don’t strike out many guys but do produce a ton of groundballs. They’ll pitch with a lot of runners on base (also known as “traffic”), but as commentators will often say, “They are one pitch away from getting out of this inning,” because their propensity for inducing ground balls can easily result in a double play. Sinkerballers tend to not give up many home runs, either.

There are a number of different grips for a two-seam fastball. See where the two curves of the horseshoes come closest together, almost parallel to one another? That’s where you’re going to want to put your fingers.

Typically, you put your fingers with the seams so that one seam is running under each finger. You can grip on the seams or inside the seams, it’s up to you. An alternative grip that’s not as common is to have your fingers go across the seams. Fiddle around with it and go with what feels most comfortable to you.

The most important part of the two-seamer is the follow-through. That’s how you make the ball “sink” or drop at the end. You want to follow-through as far as you can and then pronate your wrist at the end so that your palm is facing towards the 3 o’clock position. If done properly, the spin will cause the ball to move down-and-in on a right handed batter.

Cutter

The cut fastball has grown in popularity over the past decade. If you wanted good sports wagering strategies, odds are the best cutter in the game belongs to Yankees closer Mariano Rivera. He has made a living off this one pitch. It’s so good that it’s all he needs to throw. Opposing hitters know it’s coming, and they still can’t hit it. It’s that good. Like the sinker, the cutter isn’t designed to be a swing-and-miss pitch. The cutter is meant to be hit, it’s just not meant to be hit well.

A cutter “cuts” at the last second, making it hard for a batter to square up. The batter swings, thinking the ball will be in one spot, but that last-second cut makes the ball dart away from the barrel. Instead of hitting the ball with the fat part of the barrel, the hitter connects with either the end of the bat or the handle.

The result is a weak groundball, stung hands, oftentimes a broken bat, and muttered curses, especially if it’s cold out. A cutter thrown by a right-hander will cut away from a right-handed batter and into a left-handed one.

A lefty cutter will do the opposite. A pitcher’s cutter will be slightly slower than his four-seamer. Major league cut fastballs are typically 88-91 mph while Rivera’s is in the low 90s.

The most typical cut fastball grip is similar to a two-seam fastball (although you can hold it like a four-seamer as well). Take a standard two-seam grip and shift it slightly off-center, putting more pressure on your middle finger. Be careful not to put too much pressure on that finger; you don’t want to grip it too tightly.

You just want more pressure on your middle finger than on your index finger. That will cause the side spin that makes the ball “cut”. You can also slide your thumb up towards the inside part of the ball (moving it up towards your index finger a bit instead of having it directly under the baseball).

You don’t need to do anything special when you release the ball; just release it like you would a normal fastball. You don’t need to turn your wrist like you would a curveball, for example. The pressure placed on the outside of the ball by your middle finger is what makes the ball move.

Splitter

The split-fingered fastball, or splitter, has been a lifesaver for many a pitcher who had been floundering in the minor leagues. The pitch is so devastating that it has allowed many pitchers who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to reach the majors achieve their dreams of becoming major league ballplayers.

It is a high-risk/high-reward pitch because while it is extremely effective, if it is not thrown properly, it can be very hard on the elbow. Its name is misleading because it’s not really a fastball. The splitter is an off-speed pitch that is typically thrown in the mid-to upper-80s.

The splitter is perhaps the ultimate strikeout pitch because it is so hard for hitters to lay off of, let alone hit. The splitter looks exactly like a fastball but drops off the table as it reaches the plate. It’s not designed to be thrown for a strike; the goal of the splitter is to get the hitter to chase it out of the strike zone.

The splitter is usually a pitcher’s “out pitch”, meaning that it’s what a pitcher uses to finish a hitter off and get a strikeout. When a batter has two strikes, he has to protect the plate and swing at anything close that could be a strike. Well, the split-fingered fastball looks like a fastball. The hitter decides to swing at it, but then the ball drops and the hitter flails away at a pitch out of the strike zone.

As the name suggests, you have to use a split-fingered grip for the splitter.Grip it the same way you would a two-seam fastball, then spread your index and middle fingers outside the seams, making sure your thumb is directly under the baseball. Like a cutter, you don’t need to do anything special with your wrist. In fact, you don’t want to twist your wrist in any way; that’s how you put strain on your elbow. As with any pitch, follow through is important.

Change-up

The change-up is one of the most effective, yet underutilized, pitches in baseball. It’s not complicated to throw and carries none of the injury risk of breaking pitches, yet it’s not nearly as glamorous as a curveball or slider.

Trevor Hoffman used his change-up to set the all-time saves record and if I were to wager on MLB, betting lines would be in my favor he’ll be enshrined in the despite not throwing harder than 87 mph. The change-up relies solely on deception rather than movement, although a few pitches can get their change-ups to move.

A curveball is about 10 mph slower than your fastball, and that speed disparity throws off a hitter’s timing. To a hitter, the change-up looks exactly like a fastball. By the time they realize the difference, it will be too late. They’ve already started their swing and will be way out in front of the ball. If they do hit the change-up, they will either pull it foul or hit the ball weakly somewhere.

There are several different variations of the change-up, but this is one of the most common: the circle change. Make the “ok” sign with your hand, forming a circle with your thumb and index fingers. Then, grip the baseball with your three other fingers. That should put the circle on the side of the ball.

Simply throw the ball the same way you would throw a fastball and let the grip do the work. For a more advanced pitch, pronate your wrist at the end when you release. That will give the ball some sink.

The key to throwing an effective change-up is arm speed. The change relies on deceiving the hitter, and that cannot be done without arm speed. You have to have the same arm speed that you have with your fastball. If it’s slower, that will tip off the hitter that a change-up is coming.

Don’t try and slow the pitch down by reducing your arm speed. Let the grip take care of that. The extra drag on the ball from your hand is what slows it down. A great way to work on this is to throw your change-up while doing long toss. You’ll have to use fastball arm speed in order to get the ball that far. Greg Maddux used to do this with his change-up.

Curveball

Now we’re getting into pitches that are commonly referred to as “breaking stuff”. As the name implies, these pitches “break” and have a lot of movement. They use that movement to fool hitters and get them to swing-and-miss. While fastballs and change-ups move also move, they are generally not considered “breaking pitches”.

Anyway, the curveball is probably the most well-known breaking ball. For those of you who play tennis and understand topspin, a curveball uses the same principle. Basically, a curveball is just putting topspin on a ball with your hand instead of a racquet. The curveball’s effectiveness comes from its speed, or lack thereof, and movement.

A curveball is typically 10-15 mph slower than your fastball, so the hitter’s timing is thrown off. Plus, the ball isn’t coming in straight. Coming out of a pitcher’s hand, a curveball often initially looks like it’s coming straight at you, only to curve back into the strike zone. Whenever you see a batter’s knees buckle, that why. He thought the pitch was coming at him and flinched.

The curveball is a tricky pitch to throw because unlike the previously mentioned pitches, throwing a curveball involves turning your wrist. To grip a curveball, you’re going to want to put your middle finger on one of the elongated sides of one of the horseshoes. Take a four-seam grip and then rotate the ball horizontally 90 degrees. Your finger should be laying along one of the seams. Move your thumb a bit towards the inside of the ball so it’s resting on another seam that is on the opposite corner from your middle finger. For a righty, that would mean your middle finger is on the upper-right seam while your thumb is on the lower-left seam.

Now the release is where it gets tricky. As you draw your arm back, you need to be thinking “fastball, fastball, fastball, curveball.” What that means is that everything is exactly the same as it would be if you are throwing fastball. As you draw the ball back from your glove, nothing is different. As your arm comes forward you want to turn your wrist– a good rule of thumb is to do it around the time your arm comes in line with your head.

For a fastball, your palm would be facing home plate as if you were trying to give it a high five. For a curveball, your palm is facing your head so that it’s like you’re doing a karate chop or signaling “first down” towards home plate. You want to keep your fingers on top of the ball, and when it comes time to release the pitch, it’s almost like you are snapping your fingers: pull your middle finger down as you push your thumb up. Spin the ball of your fingers, and then make sure to really extend and follow through. That’s it; you don’t snap or turn your wrist.

Just make sure to keep your arm speed up for two reasons: one, it adds to the deception of the pitch and keeps you from tipping off the hitter. If you slow your arm down, the hitter will pick up on the difference and know that a fastball isn’t coming. The second reason is that it adds more bite to the pitch and makes it more effective. The curveball’s lesser speed is caused by the grip and how you throw it, not by trying to throw it slower.

A variation of the curveball is the knuckle curve. It’s thrown the same way except you tuck your index finger in so that the knuckle closest to your fingertip is pressing down into the ball. It takes some getting used to, but it does seem to be easier to get spin.

Slider

The slider is the curveball’s cousin and is the preferred off-speed pitch of many power relievers as well as sinkerball pitchers. It is faster than a curveball, and while it doesn’t have as big of a break as a curve, it has a sharper, tighter break. A slider moves in two planes: both vertically and horizontally. It’ll dive down-and-away from a right-handed batter when thrown by a right-handed pitcher.

Basically, you throw a slider by throwing a fastball while using a fastball grip. When you release the ball, be sure to extend towards the plate. The ball will be off-center in your hand because of the grip, and when you release it, you’ll be able to pull around and down on the ball, giving it that tight slider spin.